Niko J. Kallianiotis for The New York Times

The lacrosse player George Downey is part of a study testing whether Viagra can give athletes a competitive advantage.

Published: November 22, 2008

SCRANTON, Pa. — When George Downey volunteered along with other lacrosse players at Marywood University to take Viagra for a study, he received a snickering nickname from his high school coach. His parents jokingly told their friends. Inquiring minds sent messages to his Facebook page.

Niko J. Kallianiotis for The New York Times

Kenneth W. Rundell, lead researcher of the Marywood study, said Viagra “provides an unfair advantage, at least at altitude.”

“They’re making fun of me,” Mr. Downey, 19, said good-naturedly. “Deep down, I think they’re looking for tips.”

Except that the Marywood study does not involve the bedroom, but the playing field. It is being financed by the World Anti-Doping Agency, which is investigating whether the diamond-shaped blue pills create an unfair competitive advantage in dilating an athlete’s blood vessels and unduly increasing oxygen-carrying capacity. If so, the agency will consider banning the drug.

Viagra, or sildenafil citrate, was devised to treat pulmonary hypertension, or high blood pressure in arteries of the lungs. The drug works by suppressing an enzyme that controls blood flow, allowing the vessels to relax and widen. The same mechanism facilitates blood flow into the penis of impotent men. In the case of athletes, increased cardiac output and more efficient transport of oxygenated fuel to the muscles can enhance endurance.

“Basically, it allows you to compete with a sea level, or near-sea level, aerobic capacity at altitude,” Kenneth W. Rundell, the director of the Human Performance Laboratory at Marywood, said of Viagra.

Some experts are more skeptical. Anthony Butch, the director of the Olympic drug-testing lab at U.C.L.A., said it would be “extremely difficult, if not impossible” to prove that Viagra provided a competitive edge, given that the differences in performance would be slight and that athletes would probably take it in combination with other drugs. Scientists have the same uncertainty about the performance-enhancing effects of human growth hormone, though it is banned. But some athletes do not need proof — only a belief — that a drug works before using it, Dr. Butch said.

“I think it’s going to be a problem,” he said.

Through the decades, athletes have tried everything from strychnine to bulls’ testicles to veterinary steroids in a desperate, and frequently illicit, effort to gain an advantage. Several years ago, word spread that Viagra was being given to dogs at racetracks, said Travis Tygart, the chief executive of the United States Anti-Doping Agency, based in Colorado Springs.

Interest in the drug among antidoping experts was further increased by a study conducted at Stanford University and published in 2006 in The Journal of Applied Physiology. The study indicated that some participants taking Viagra improved their performances by nearly 40 percent in 10-kilometer cycling time trials conducted at a simulated altitude of 12,700 feet — a height far above general elite athletic competition. Viagra did not significantly enhance performance at sea level, where blood vessels are fully dilated in healthy athletes.

A 2004 German study of climbers at 17,200 feet at a Mount Everest base camp, published in The Annals of Internal Medicine, found that Viagra relieved constriction of blood vessels in the lungs and increased maximum exercise capacity.

At this point, there is no evidence of widespread use of Viagra by elite athletes, Mr. Tygart said. Yet, because the drug is not prohibited and thus not screened for, there is no way to know precisely how popular it is.

There is some suspicion that Viagra may be used to circumvent doping controls in cycling, which has faced waves of scandal. Last May, the cyclist Andrea Moletta was removed from the Tour of Italy after a search of his father’s car turned up 82 Viagra pills, as well as syringes concealed in a tube of toothpaste, according to news accounts. An investigation ended without formal accusations of doping.

The former major league baseball player Rafael Palmeiro once served as a pitchman for Viagra and tested positive in 2005 for the steroid stanozolol, although the connection, if any, between the drugs in his case is not known. Some athletes are believed to take Viagra in an attempt to aid the delivery of steroids to the muscles and hasten recovery from workouts. Others take Viagra to counter the effects of impotence brought on by steroid use, said Dr. Gary I. Wadler, the chairman of the World Anti-Doping Agency’s committee on prohibited substances.

The agency, based in Montreal, is financing two studies related to Viagra and performance enhancement in sports. The University of Miami is studying whether Viagra benefits aerobic capacity at lower altitudes than the Stanford study — comparable to heights where elite competitions take place. This study is also examining whether there is a difference in the way Viagra affects male and female athletes.

The study at Marywood University is measuring the potential effects of Viagra as an antidote to air pollution, produced outdoors by the exhaust of factories and automobiles and indoors by ice-resurfacing machines. Studies involving animals, and children in Mexico City, have indicated that pollution causes pulmonary hypertension. If that could be alleviated for athletes by Viagra, “performance is going to be enhanced,” said Dr. Rundell, the lead researcher of the pollution study.

The Marywood study is expected to be completed by next month, and the Miami study is expected to conclude in February. The earliest that the World Anti-Doping Agency could place Viagra on its list of prohibited substances would be September 2009, five months before the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, British Columbia, a spokesman said.

“My guess is, it’s a pretty easy decision to make,” Dr. Rundell said. “It’s a compound that’s pretty easily measured. And it clearly provides an unfair advantage, at least at altitude. I couldn’t imagine it not going down on the list, but I’m not the one who makes those decisions.”

Because the air in Beijing is so polluted, some suspected that Viagra would be a popular drug at the 2008 Olympics. But there was no attempt to measure its presence because it was not prohibited, a spokeswoman for the International Olympic Committee said.

Even if Viagra increases athletic stamina by a small amount, it could have a significant effect on results in sports like distance running, or cycling and Nordic skiing, whose events can be held at altitudes of 6,000 feet or above, Dr. Rundell said. He noted that the time between first place and fourth place in the 15-kilometer cross-country ski race at the 2006 Turin Olympics amounted to a performance differential of less than 1 percent.

Even athletes in contact sports may benefit from Viagra, Dr. Rundell said. “If you are a football player going to Denver from Atlanta, I don’t see why it wouldn’t work,” he said.

Anne L. Friedlander, an author of the 2006 Stanford study, said that she expected Viagra would be banned for sports use. But, she noted, it does not benefit everyone. Only 4 of the 10 participants in her study responded to the drug. And Viagra merely elevated the performance of those four to the level of other participants less affected by altitude, rather than enhancing performance beyond normal, the way steroids do, Dr. Friedlander said.

“That’s something to think about,” she said.

Whether Viagra is allowed or prohibited, it remains illegal for athletes to use prescription medication not ordered for them, Mr. Tygart of Usada said. He and others cautioned that the use of Viagra could also result in side effects like severe headaches, changes in vision and priapism, which may require medical attention.

Meanwhile, at Marywood University, Mr. Downey and about a half-dozen other lacrosse players have joined a group of 30 participants in the study of Viagra’s effectiveness in countering air pollution. They will ride exercise bikes in clean air and in a room with the air polluted by the exhaust of leaf blowers and lawnmowers. And they will continue to endure teasing from their friends.

“It may take awhile to live this one down,” Mr. Downey said.

At least the participants are allowed to receive a stipend.

“You’ve got to pay for college somehow,” he said.

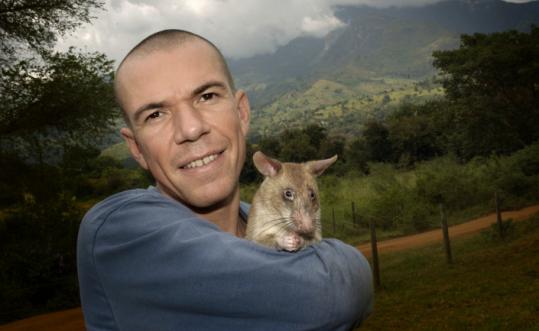

Bart Weetjens in Tanzania with one of his trained rats. (Sylvain Piraux/Apopo International)

Bart Weetjens in Tanzania with one of his trained rats. (Sylvain Piraux/Apopo International)