Mankind's new best friend? Trained giant rats sniff out land mines, tuberculosis

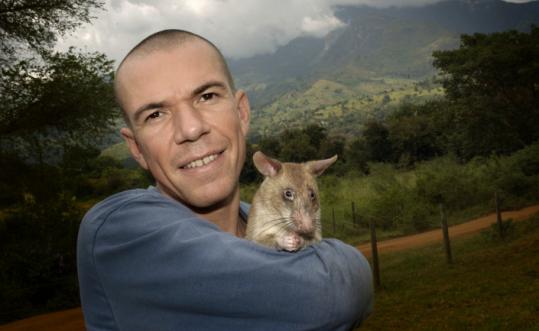

Bart Weetjens in Tanzania with one of his trained rats. (Sylvain Piraux/Apopo International)

Bart Weetjens in Tanzania with one of his trained rats. (Sylvain Piraux/Apopo International) Reviled as vermin through the ages, rats are becoming unlikely soldiers in the struggle against two scourges of the developing world: land mines and tuberculosis.

In Mozambique, special squads of raccoon-size rats are sniffing out lethal explosive devices buried across the countryside, remnants of the country's anticolonial and civil wars of the last century.

In neighboring Tanzania, teams of rats use their twitchy noses to detect TB bacteria in saliva samples from four clinics serving slum neighborhoods. So far this year, the 25 rats trained for the pilot medical project have identified 300 cases of early-stage TB - infections missed by lab technicians with their microscopes. If not for the rodents, many of these victims would have died and others would have spread the disease.

"It's fair, I think, to call these animals 'hero rats,' " said Bart Weetjens, the Belgian conceiver of both programs.

The rat squads, at first derided by some interna tional aid officials as ridiculous, have won support from the World Bank and praise from the UN and land mine eradication groups. Now there are plans to deploy the creatures to Angola, Congo, Zambia, and other land mine-infested lands.

The rats' "noses are far more sensitive than all current mechanical vapor detectors," Havard Bach, a mine-clearing specialist with the Geneva International Center for Humanitarian Demining, wrote in a study.

Although rats make almost everyone's short list of horrors - associated with filth, disease, and destruction of food crops - they "are really nice creatures," according to Weetjens.

"They are organized, sensitive, sociable, and smart," said the former product engineer in a telephone interview from Antwerp, Belgium, home base for Apopo International, the nonprofit organization that trains and deploys the rats.

In the 1990s, he journeyed to Africa to study land mine clearance techniques. He put his engineer's mind to the expensive, clumsy, and often risky methods employed to detect the lethal contraptions of metal and explosive that detonate underfoot.

Land mines claim casualties for decades after the last shot is fired in a conflict; millions are strewn in former and present fighting zones across Africa, Asia, and Europe. The wickedly durable antipersonnel devices kill or maim thousands of people every year, mainly in the poorest of countries. Removal of the weapons is a priority of the United Nations and other groups.

"In Africa, it came to me: Rats can be part of this great effort," Weetjens recalled.

So he started training giant pouched rats - an African species known for its large size, sunny disposition, and ultra-keen nostrils - to detect the faintest whiff of TNT and other explosives. Because the rats are too light to trigger the explosive, they are not harmed in the exercise; they simply signal the location of the explosive to a handler, who has it defused and removed.

The rat land mine-clearing program in Mozambique, although still small in scale, has been operational for two years - with 34 trained rats deployed to the field, each overseen by a pair of armor-clad handlers. Another 250 mine-detecting rats are undergoing schooling at Tanzania's Sokoine University of Agriculture. It takes 8 to 10 months to fully train a rat, said Weetjens.

A single rat can inspect 1,000 square feet in about 30 minutes, according to Apopo; that's at least a full day's labor for a human working with an electronic detector at terrible risk.

Rat teams are credited with clearing 270 square miles of former farm and village land in southern Mozambique, allowing for the return of peasant families dislocated since the 1980s.

Dogs can perform the same task. But rats are less expensive to train ($3,000 to $5,000 per animal, compared with $40,000 for a canine), easier to house and transport, and far less susceptible to tropical disease. Also, dogs can trip land mines.

Also, rats don't form deep emotional attachments to a single handler. A rat will happily work with anyone who gives the right commands and provides the correct payoff - a few peanuts or a nice ripe banana for locating a land mine, said Andrew Sully, Mozambique program manager for Apopo.

The rodents are hitched to a light leash and scamper in tight grid patterns in suspected land mine sites. When they scent explosive, they signal with furious digging motions. They typically work from 5 to 9 a.m., quitting when the ferocious African sun gets too hot.

"People are so surprised to see this" project, said Alberto Jorge Chambe, a Mozambican rat handler for Apopo. "Rats are usually considered pests or enemies of humanity. But rats are helping my country escape the shadow of death."

Meanwhile, in a conceptual leap, Weetjens decided to turn the rats' sharp olfactory sense to disease detection, starting with tuberculosis. "The medical applications, I believe, will eventually prove even more important than the hunt for land mines," he predicted.

In the pilot project in the Tanzanian capital of Dar es Salaam and the nearby city of Morogoro, Apopo-trained rats evaluate saliva samples at a rate of 40 every 10 minutes; that's equal to what a skilled lab technician, using a microscope, can effectively complete in a day.

A TB rat signals with unmistakable paw motions when it detects sputum infected by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the infectious bug responsible for 1.7 million deaths and 9.2 million new TB cases each year, mainly in poor countries, according to the World Health Organization. Scientists at Germany's Max Planck Institute are now trying to determine whether the rats are detecting the scent of the actual TB bacteria or some metabolic reaction produced by the infection.

For both TB and land mines, the rats are trained to respond to the sound of a clicker; when the rat makes the scratching motion that means it has detected an explosive or the odor of disease, the handler or trainer responds by snapping the clicker, which means a nut or fruit is on the way.

So why don't the animals just scratch every few minutes to win a treat?

"That would be human behavior," said Weetjens. "Rats are more honest."

Colin Nickerson can be reached at nickerson.colin@gmail.com.![]()

0 comments:

Post a Comment