Think of a Roth as the mirror image of a regular IRA or 401(k): Instead of collecting a tax benefit up front, you get your break at the back end. When you fund a traditional IRA, you can take an immediate tax deduction on your contributions, but you then pay income taxes when you pull your money out. When you open a Roth IRA you're not entitled to a deduction, but you can withdraw all your money, including earnings, tax-free. The Roth 401(k) works the same way.

Mathematically, there's no difference between getting a tax break at the beginning or end. All else being equal, you end up in the same place whether you pay taxes at the outset or in retirement.

By Walter Updegrave, Illustrations by Christoph Niemann

2. Why would I pick a Roth?

Because in the real world, all else is rarely equal. Two wrinkles can give a Roth the edge. The first stems from the fact that Congress set the same contribution limits for Roths as for regular 401(k)s and IRAs, and that nuance means you can effectively shelter a larger sum from taxes in a Roth.

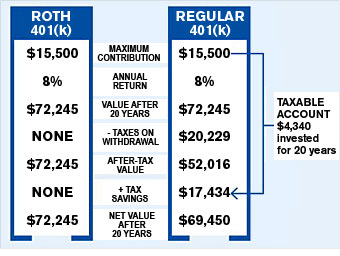

Think of it this way. If you're in the 28% bracket, contributing $15,500 in after-tax dollars to a Roth is the equivalent of socking away $21,528 in pretax dollars in a regular 401(k) because you'll have to pay taxes eventually on the regular plan's withdrawals. But you can't put that much in a 401(k). To match the Roth, you'd have to put $15,500 in a your regular 401(k) and then invest the remaining $6,028 outside the plan. You'd owe income taxes on that $6,028, which leaves you with $4,340 in a taxable account (where taxes will drag down your returns).

As the graphic shows, the combined after-tax value of your 401(k) and taxable account would be smaller than the Roth's tax-free balance.

One warning: If you switch your $15,500 from a regular 401(k) to a Roth 401(k), every other week your paycheck will be $167 smaller (at a 28% tax rate) because of lost tax savings.

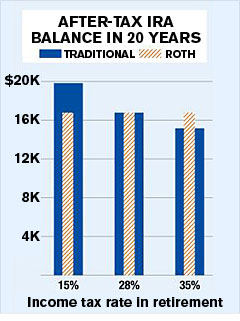

The second wrinkle is changing tax rates. This example assumes that you'll be in the same tax bracket when you retire as you are today. But if your rate is higher in retirement, a Roth becomes an even better deal because you paid taxes at today's relatively low rate. If you fall into a lower tax bracket, paying taxes later would likely win out.

3. How can I know my future tax bracket?

It's tough. Your future tax rate will depend, among other things, on the arc of your earnings over your career and what Congress does to tax rates.

Typically, you're in the lowest bracket you'll ever see when you're young and your income is modest, making the Roth a better bet. Even if you're in mid-career or later, don't assume you'll drop into a lower tax bracket. In retirement, much of your income will consist of 401(k) and IRA withdrawals and, possibly, a pension. But since you're no longer reducing your taxable income by contributing to 401(k)s and IRAs, you could end up in the same tax bracket, if not a higher one.

This uncertainty provides yet another reason to put at least some money in a Roth. The concept is simple: Just as it pays to spread your retirement savings among different types of stocks and bonds, it makes sense to diversify your tax exposure. You'll pay ordinary income tax on withdrawals from regular 401(k)s and IRAs. If your entire portfolio is in such accounts, you could lose as much as 35% to taxes. If Congress raises tax rates, your spendable income will shrink even more.

Funding a Roth allows you to hedge that risk. It also gives you more flexibility to manage your tax bill. If a larger-than-usual one-time withdrawal from your 401(k) will push you into a higher tax bracket, you can avoid the bigger tax hit by pulling tax-free money from your Roth instead.

. Will Congress take away the tax benefits?

Even a Roth can't immunize you from every conceivable tax hit. It's possible that a future Congress could change the rules by, say, taxing consumption instead of income, which could make Roth withdrawals taxable. But outright reneging on the promise of tax-free Roth withdrawals seems unlikely, at least without some transition or grandfathering rules. What's more likely is that Congress will simply raise income tax rates, putting the burden on wage earners and retirees pulling money from regular IRAs and 401(k)s.

NEXT: Can I open a Roth? 5. Can I open a Roth?

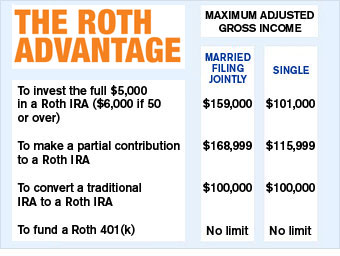

No matter your income, you can fund a Roth 401(k) if your employer offers the option. Roughly 25% of companies do now, and more than 60% of those surveyed last year by the Profit Sharing/ 401(k) Council of America said they either plan to roll out one or are considering it.

The contribution limits for Roth 401(k)s are the same as for regular 401(k)s: $15,500 this year, plus $5,000 in catch-up contributions if you are 50 or older. As for the Roth IRA, eligibility comes down solely to how much you make, as you can see in the table at right.

By the way, there's nothing to prevent you from splitting your 401(k) funds between a regular and a Roth 401(k), although if you decide to do that, remember that any matching funds your employer kicks in will go to a regular 401(k). Similarly, assuming you qualify for both types of accounts, you can also divvy up your IRA contribution between a traditional IRA and a Roth.

NEXT: Can I move my old IRAs into a Roth? 6. Can I move my old IRAs into a Roth?

Indeed you can, by simply transferring your traditional IRA into a Roth IRA. This year and next you'll have to meet income-eligibility rules - your modified adjusted gross income (whether you're single or married) can't exceed $100,000 the year you convert.

Two years ago, though, in a burst of magnanimity (that will also raise tax revenue), Congress eliminated the income test starting in 2010. At that point, you'll be able to convert regardless of how much you earn. This legislation doesn't change the income-eligibility rules for making annual contributions to a Roth, but it does provide an easy way around them: Open a deductible IRA (if you qualify) or nondeductible IRA (which anyone with earned income can do) this year and next and then convert to a Roth in 2010.

Of course, the U.S. Treasury isn't going to just let you skate on a tax bill by shifting money into a Roth. When you convert, you'll owe income taxes on the rollover, although if your conversion includes nondeductible IRA contributions, you won't owe taxes on those amounts again. As to whether it pays to make the change, the calculus is virtually the same as deciding between contributing to a regular 401(k) or IRA and a Roth: It all comes down to taxes now or taxes later. To run the math, use the conversion calculator at

dinkytown.net.

NEXT: Can I convert my 401(k) to a Roth? 7. Can I convert my 401(k) to a Roth?

Until you change jobs or retire, you typically can't roll your 401(k) into a Roth IRA. And you can't convert your plan into a Roth 401(k). But between jobs or at retirement (at 55 or older), you're free to switch your 401(k) to a Roth IRA as long as your income allows it ($100,000 or less until 2010). New in 2008: You no longer have to first roll it over into a traditional IRA and then convert it. You can now go directly.

NEXT: How do taxes work with Roth conversions? 8. How do taxes work with Roth conversions?

You may encounter more than a few sticky tax challenges when you convert. The first is how you'll pay the tax bill. You could use some of the IRA or 401(k) balance, but a conversion is more likely to pay off if you foot the bill with outside funds. Indeed, if you're under 591/2, you'll pay a 10% early-withdrawal penalty on the funds you tap to pay the taxes, eroding the benefits of making the swap.

You also need to think about what converting will do to your overall income tax bill. Even though the amount you convert doesn't affect your eligibility (if your AGI is $97,000 and you convert a $20,000 IRA, that doesn't push you over the $100,000 cap), it's considered taxable income. So a large 401(k) or IRA could nudge you into a higher bracket. In that case, convert smaller amounts over a few years or wait until you're in a lower bracket.

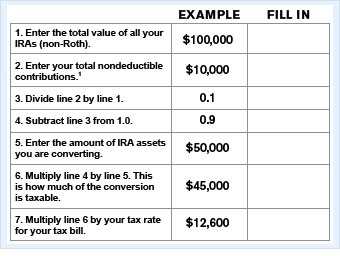

Finally, if you've ever opened a nondeductible IRA - or rolled a 401(k) with after-tax contributions into an IRA - you might think you could avoid taxes by converting only those after-tax dollars. Nice try, but you can't cherrypick funds. When you move just a piece of your IRA money into a Roth, for tax purposes the amount you convert is considered to have the same blend of pretax and after-tax dollars as all of your non-Roth IRAs. That could leave you with a complicated tax bill if you are converting just a portion of your IRA funds. You can use the worksheet to figure it out.

NEXT: What if I convert and then the market tanks? 9. What if I convert and then the market tanks?

You get a do-over. Really. Around the IRS, the second chance goes by the more technical name "recharacterization." Essentially, you can undo the conversion and return your money (plus earnings, if any) to a traditional IRA, then reconvert later. This option can come in handy if the market stumbles (or you find you don't have enough money to pay the conversion taxes).

Suppose you convert a $100,000 IRA to a Roth and shortly afterward the value drops to $80,000. Even though your Roth is worth 20% less, you'll still owe taxes based on its value on the conversion date, or $28,000 assuming you're in the 28% bracket. By recharacterizing, however, you can move the $80,000 back into a regular IRA and reconvert later. Assuming your IRA is still worth $80,000, your next conversion will cost you $22,400, leaving you with the same amount in the Roth but saving you $5,600 in taxes.

You can undo a conversion anytime up to the filing deadline, including extensions. So if you converted in the 2008 tax year, you can switch back as late as Oct. 15, 2009. If you want to switch into a Roth again, you must wait until the year after your original conversion (2009 in this example), and you must wait 31 days after you did the recharacterization.

NEXT: How will a Roth affect my Social Security10. How will a Roth affect my Social Security?

Another compelling reason to fund a Roth IRA is that you may be able to hold on to more of your Social Security check in retirement. As much as 85% of Social Security benefits become taxable if your income exceeds certain thresholds. In determining those levels, the IRS includes half your Social Security benefit, any income from a retirement job, pension payments, investment earnings and withdrawals from regular 401(k)s and IRAs.

But withdrawals from Roths are excluded from this calculation. So by pulling money from a Roth account instead of other sources, you may be able to protect some or all of your Social Security check from the IRS, thus boosting your after-tax income in a given year.

NEXT: When do I have to withdraw from a Roth? 11. When do I have to withdraw from a Roth?

You don't. With regular IRAs, you must begin withdrawing at least a minimum amount of money no later than the April after you turn 701/2, whether you want to or not. Fail to do so, and you'll be hit with a stiff penalty.

Not with your Roth IRA. You never

have to take a penny out. You can let your savings rack up tax-free returns as long as you want. That can be a huge advantage if you have enough in other funds to live on and want to keep your Roth stash as an emergency reserve. If it turns out you don't have to tap your Roth, you can pass it along to your children, who can take the money right away or stretch withdrawals (and tax-free growth) over the rest of their lives. If your spouse inherits, she isn't required to make withdrawals at all.

NEXT: How easy is it to get money out of a Roth? 12. How easy is it to get money out of a Roth?

With any retirement account, you must clear some hurdles to get at your money. By those standards, Roth withdrawal rules aren't draconian. In fact, you can take out your Roth IRA contributions at any time without paying taxes or a 10% early-withdrawal penalty. You can withdraw your Roth earnings without taxes or penalty as long as you're 591/2 or older and you've had a Roth IRA for at least five years. The rules for a Roth 401(k) are similar, but as a practical matter you can't touch your money until you leave your job.

What if you need the cash sooner? Once you've had a Roth IRA for five years, you can withdraw your earnings without paying taxes or a penalty if you become disabled or are buying your first home ($10,000 max); you can also take out money penalty-free for certain education costs, though you will owe taxes on your gains. A Roth 401(k) allows for tax and penalty-free withdrawals for disability only.

black screen when turned off.

black screen when turned off.

The Patriots drafted Matt Cassel in the seventh round (230th overall) of the 2005 NFL Draft. The 6-foot-2-inch, 222-pound quarterback backed up two Heisman Trophy winners at Southern Cal in Carson Palmer, now of the Cincinnati Bengals, and current USC signal caller Matt Leinart. The California native was impressive in training camp and shined in his first preseason contest by completing 13 of 21 passes for 135 yards and a touchdown against the Bengals. Cassel saw significant action on January 1, 2006 against the Miami Dolphins where he completed 11 of 20 passes for 168 yards and two touchdowns, registering a 116.2 quarterback rating. Cassel sat down with us to look at his life both on and off the football field.

The Patriots drafted Matt Cassel in the seventh round (230th overall) of the 2005 NFL Draft. The 6-foot-2-inch, 222-pound quarterback backed up two Heisman Trophy winners at Southern Cal in Carson Palmer, now of the Cincinnati Bengals, and current USC signal caller Matt Leinart. The California native was impressive in training camp and shined in his first preseason contest by completing 13 of 21 passes for 135 yards and a touchdown against the Bengals. Cassel saw significant action on January 1, 2006 against the Miami Dolphins where he completed 11 of 20 passes for 168 yards and two touchdowns, registering a 116.2 quarterback rating. Cassel sat down with us to look at his life both on and off the football field.